JLR: Gene therapy shows promise for deadly childhood disorder

Babies with the rare, deadly genetic disorder Sandhoff disease begin to miss developmental milestones just months after birth. Lacking muscle tone, they never learn to sit up; they develop heads too large to lift and eventually suffer uncontrollable seizures. There is no cure.

of the National Human Genome Research Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, studies the disease. “With excellent supportive care, children can survive until age 5 or so,” she said.

in the Journal of Lipid Research by senior investigators Tifft and and lead author of the NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and their colleagues describes an important step toward gene therapy for children with Sandhoff disease.

The disease is a lysosomal storage disorder. Enzymes in the lysosome normally break down unneeded molecules. When an enzyme doesn’t work, the molecule it should degrade begins to accumulate.

Sandhoff disease disrupts the function of an enzyme that breaks down complex lipids called gangliosides. Ganglioside accumulation eventually causes cell death in the brain and spinal cord.

The first human model

The researchers wanted to know whether the problems that appear soon after birth in Sandhoff patients actually develop during pregnancy. The disease is so rare that Tifft estimates five children are born with it in the U.S. each year. Therefore, most of what is known about the disease comes from studying genetically engineered mice, which are not a perfect comparison.

This study began when a baby with Sandhoff disease came to Tifft’s clinic, where the medical geneticist treats patients with infantile and milder adult-onset forms of the disease. Researchers took skin cells from the baby and reprogrammed them into induced pluripotent stem cells. Those cells, like the ones in an embryo, can mature into any cell type in the body.

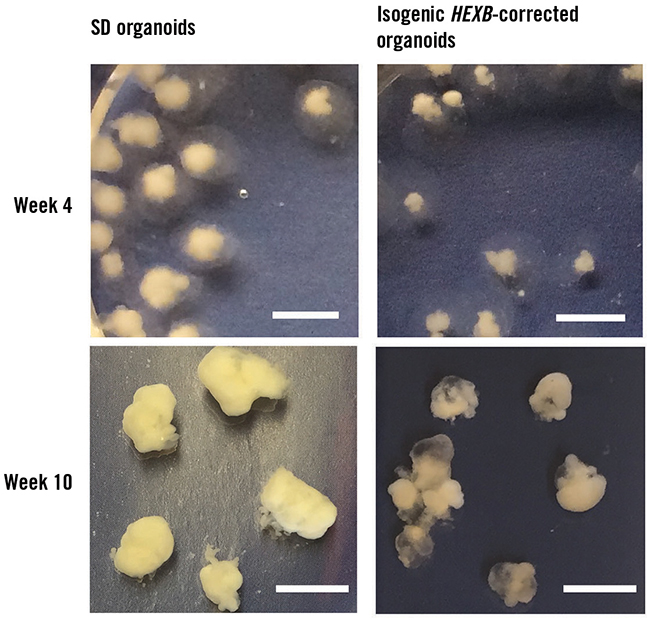

The team created healthy control cells by using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to correct one copy of the affected gene in the patient’s stem cells. The researchers then induced the two sets of stem cells to grow into simple groups of brain cells, organoids about the size of a pencil eraser. The researchers compared the healthy and Sandhoff-affected organoids to find out how the disturbed enzyme might affect early development.

Unexpected problems

As expected, researchers saw accumulation of ganglioside molecules in the Sandhoff organoids. The healthy organoids did not show this accumulation, confirming that the genetic intervention had worked. But the researchers also found something surprising.

“The major feature of this disease, in humans and in mouse models, is the neurodegeneration,” Proia said. Instead of cell death in the Sandhoff disease organoids, the researchers saw cell overgrowth. Although there was no difference between the stem cells, the Sandhoff organoids were much larger than the healthy ones, mimicking the large brains of patients.

The profile of genes expressed in the healthy organoids looks a lot like the first trimester of pregnancy. However, the researchers found that the organoids with Sandhoff disease had changes in genes that govern cell maturation. Instead of settling into a role as differentiated adult cells, the Sandhoff cells just kept growing. It remains to be determined how the disrupted ganglioside enzyme leads to changes in gene expression.

, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, researches gangliosides in the brain but was not involved in this study. “Most of us have been thinking of lysosomal storage diseases as if everything is just fine until these molecules begin to build up,” he said. “But there has always been a bubbling issue of whether the molecules themselves have an effect, other than building up to tremendous amounts.”

Schnaar said this paper is the first to address that question, showing that disruption of gangliosides does affect brain development in humans.

A path to gene therapy

CRISPR, the researchers’ original approach to correct the gene, is still far from the clinic. Therefore, the researchers also tested a more practical gene-therapy approach that had been successful in animal models of Sandhoff disease.

They used a virus to introduce a healthy version of the gene for the gangliosidase enzyme to 4-week-old Sandhoff organoids. About two weeks after receiving the gene therapy, the organoids that had been treated were closer in size to the healthy organoids and no longer had large clumps of ganglioside.

“That’s the first proof of principle in a human model system that gene therapy may actually be beneficial for these kids,” Tifft said. The viral gene-therapy approach is in clinical studies for other lysosomal storage disorders, and the first FDA-approved gene therapy for any genetic disorder uses a similar virus.

The child whose skin cells were used for this study died at age 4. While it comes too late for her, the research strikes a hopeful note for future generations of children with Sandhoff disease.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Bacteriophage protein could make queso fresco safer

Researchers characterized the structure and function of PlyP100, a bacteriophage protein that shows promise as a food-safe antimicrobial for preventing Listeria monocytogenes growth in fresh cheeses.

Building the blueprint to block HIV

Wesley Sundquist will present his work on the HIV capsid and revolutionary drug, Lenacapavir, at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, in Maryland.

Gut microbes hijack cancer pathway in high-fat diets

Researchers at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research found that a high-fat diet increases ammonia-producing bacteria in the gut microbiome of mice, which in turn disrupts TGF-β signaling and promotes colorectal cancer.

Mapping fentanyl’s cellular footprint

Using a new imaging method, researchers at State University of New York at Buffalo traced fentanyl’s effects inside brain immune cells, revealing how the drug alters lipid droplets, pointing to new paths for addiction diagnostics.

Designing life’s building blocks with AI

Tanja Kortemme, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, will discuss her research using computational biology to engineer proteins at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Cholesterol as a novel biomarker for Fragile X syndrome

Researchers in Quebec identified lower levels of a brain cholesterol metabolite, 24-hydroxycholesterol, in patients with fragile X syndrome, a finding that could provide a simple blood-based biomarker for understanding and managing the condition.